“Get the Fuck Out!”: Performativity of the Protests’ Parlance, 2021

Warsawa

The Polish Constitutional Tribunal of October 22, 2020, ruled abortion for fetal abnormalities a violation of the Polish Constitution, imposing a near-total ban on pregnancy termination in a country where abortion laws were already among the strictest in Europe. The decision sparked the largest wave of protests since 1989 and the fall of communism, transforming the streets emptied by the fear of the pandemic into a vibrant zone of social change.

The protest wave has swept over the whole country. While Warsaw, the Polish capital, was the center of the events, the protests occurred both in major cities and smaller towns, gathering people from various age groups, genders, and sometimes even from different sides of the political spectrum. According to police data, when protests peaked on October 28, around 430,000 people in more than 400 locations expressed their objection in the streets.[1] However, while the size of the protests has caused great agitation, it is the vulgar slogans reverberating amid the infinity of the crowds that provoke outrage in public discussion.

The word that became the leading phrase for the protests was “Wypierdalać.” Translated from Polish, the word expresses a command to “get the fuck out.” Another one, equally prominent in uniting the crowds (and chanted to the rhythm of Eric Prydz’s “Call On Me”), was “Jebać PiS” (“Fuck PiS”), where “PiS” stands for the name of the Polish ruling party, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice). “Jebać PiS” has also gained popularity in a pictorial form, written as eight asterisks: ***** ***.

Although both slogans are swearwords (and, just as expressed in translation, are highly offensive), people decided to use them publicly, expressing their anger, which could no longer be processed in any refined manner. However, the slogans have been used to undermine the protests, with politicians, journalists, and linguistic experts dwelling upon their vulgarity and arguing that the boundaries of linguistic decency and propriety were crossed. National media unanimously attacked both the protests and their vulgar dimension, suggesting a cultural collapse driven by a “leftist fascism destroying Poland.” On the contrary, the liberal media, equally bemused with the scale and form of the protests, sought justification and rationalization of the performativity of the protest parlance, which is partly presented in this article. At times, the general public indignation over the use of swear words—on both sides of the political spectrum—was greater than the will to engage with the issue of restricting freedom. Indeed, it has been the first time a swear word became an official slogan of a social movement in Poland, carried on few-meters-long banners and beeped out on live TV broadcasts. Nonetheless, the uproar may be induced not by the cursing per se, but by the people engaging in this act of communication, who are mostly young women.

During the survey conducted for the purpose of this article,[2] we asked whether the respondents swore during the protests and what was their opinion on the matter. Out of 86 completed questionnaires, 39,5% of them came from people who did not exclaim profanities, while the other 60,5% felt comfortable doing so during the protests. When asked about their opinions on this form of expression, the answers ranged from highly critical to very approving. The more approving answers expressed frustration with government’s measures and pointed to the fact that it was the best way to vent their emotions, while those more disapproving implied that it was not the right language for a public debate, and that they felt uncomfortable with it. For instance, one of the respondents expressed their concern over society’s “lack of sensitivity to language, negligence of its ambiguity, subtlety, and metaphorical quality,” and another noted that “any form of radicalization is not a preferable option, since it only aggravates polarization.” In contrast, another claimed that language provides us with forms to express everything, hence—when a situation is particularly difficult and the person using the language is frustrated and angry—swearing can be justified, or perhaps even necessary.

The answers did not only focus on the language itself—they also discussed women as its users. The critique of the language of protests is undoubtedly gendered, especially given the resentments of some of the protesters. It seems that there exists an ample group of young women, who, despite their anger and disagreement with the government’s policies, have also, to some extent, internalized the traditionally female social niceties. Agata Stola, political scientist and sex educator, claims that this may be the biggest threat to the notion of Polish sisterhood. In her opinion, in current circumstances, women who prefer not to appear uncompromising, or who feel disgusted with the slogans that, as they claim, do not befit women, embody the difficulty of deflating the same convenance that has caused the situation in which young Polish women find themselves today.[3]

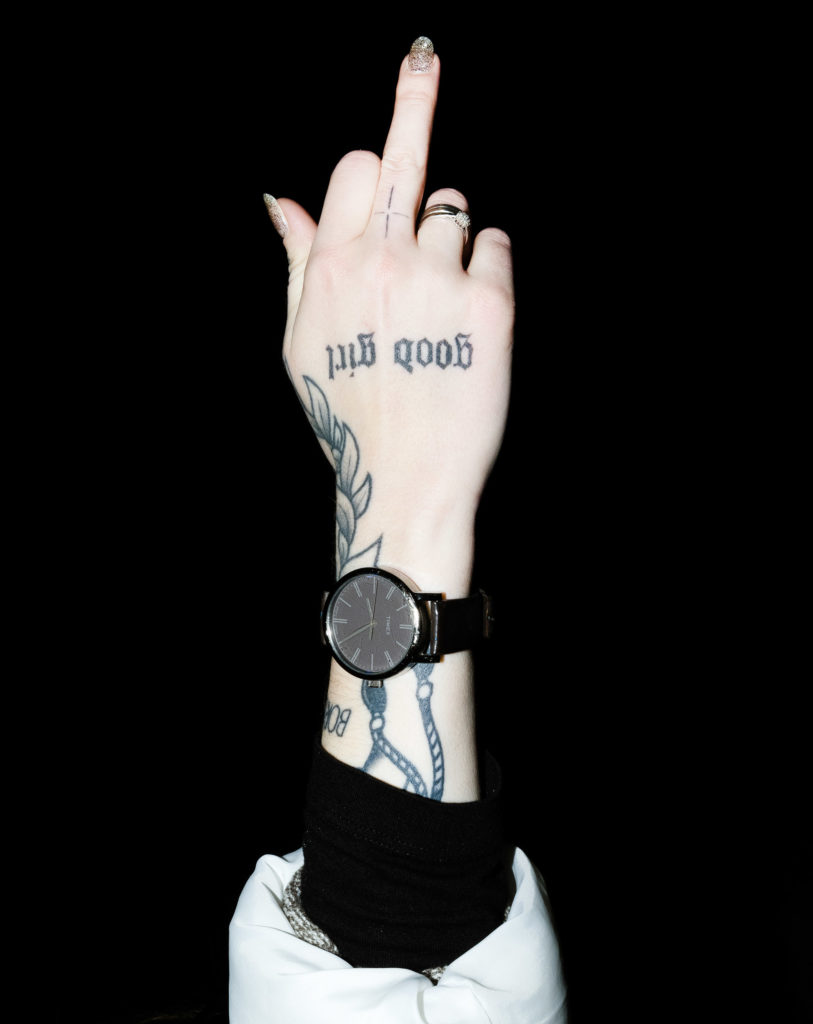

In a country where some swear words tend to be used as a proverbial comma, it comes as a surprise that a curse word used in public can cause such an outrage. The discussion of whether protesting women are allowed to use such language publicly reveals the disciplinary mechanism of denying female subjectivity. Confrontational All-Polish Women’s Strike breaks the stereotype of feminine delicacy and acquiescence. Thus, the indignation over the vulgarity of the protests paradoxically exposes the presence of the patriarchal stereotype of a “good girl.” Emma Byrne, the author of the book, Swearing Is Good for You: The Amazing Science of Bad Language, notes that although women swear just as much as men, surveys show that both of these groups tend to judge women’s swearing more harshly.[4]

By breaking the taboo and a stereotypical image of delicate women, the vulgarity of the protests forces people to reflect on the gravity of the matter and makes it a specifically female issue. It reveals a communication crisis and attempts to delegitimize power in its current form. The crude language seems only natural, for the demonstrators protested in reaction to a radical and socially unaccepted change of the law, introduced without public consultation at the very peak of the Covid-19 pandemic. Before, no one seemed to listen to women’s “polite” parlance;[5] today, they carry a long history of their suffering written on placards. Female resentment reached a crescendo in October, but it had been accumulating long and gradually.

On chilly October evenings, the calmest thing to observe was the steam coming out from the mouths of demonstrators. It seemed that the whole energy of the crowd went into screaming. The language felt like the last bastion of freedom: the freedom of expression, the liberty of opinion, and the ultimate denunciation of obedience. It felt liberating; invigorating; emancipatory. Suddenly, thousands of protesters found themselves in a position where they were not afraid to express the outrage, not only with the ruling of the court, but with the entire political situation, and they found like-minded people with whom to scream their frustrations. As explained by Timothy Jay, profanities, especially when shouted out loud, may paradoxically soothe aggression and suppress violence, becoming a valve to release tensions by articulating aggression, instead of performing a violent act in a shared affective space of rage. On top of that, Jay claims vulgarity increases pain tolerance.[6] “Wypierdalać” then both sublimates and hardens.

Although protests were attended by people of different ages, the younger generation was seen (and heard) the most. This indicated a critical moment in their political activation, especially because they had so far been often criticized for being too ignorant and dormant in times of political crisis. According to Agnieszka Graff, the controversial slogans indicate the rejection of the collective Polish identity shaped in recent decades, in alliance with the Catholic Church. The younger generation is not so constrained by history and culture, thus more confident in their fight for civil rights, and the common astonishment with the form of expression only proves the widening generational gap. That is to say, the protests, as Graff argues, are a refusal to participate in the form of statehood offered to the youngest generation through the years of transformation.[7]

The sensitivity of the youngest generation has changed. They did not have a chance to get familiarized with the “cultural” countenance of politics, as their entering into the public debate occurred after the Smoleńsk air disaster in 2010,[8] hence at a time of extreme polarization and political conflict, characterized by bitter disrespect for the opponents.[9] Since 2015, and Law and Justice victory in the parliamentary election, the political conflict between the ruling camp and the opposition has only compounded. Therefore, the Polish youth, many of whom are now protesting on the streets, are not familiar with any form of a respectable political culture. Instead, they have been taught that in politics there is no place for compromises and that using the language of contempt in public remains unpunished. Hence, the profanity exposes and mirrors the disruptive and dangerous profanation of the public debate in Poland, alongside the cartoonish parliament proceedings, grotesque media sneaking propaganda content, and depriving citizens of their rights.

Vulgar words became the umbrella slogans for postulates of the generation for whom stigmatizing and exclusive language of the ruling party is more offensive than the vulgarisms themselves.[10] Adamant parlance of the protests is an indicator of building the generational identity on emphasizing the differences, also in symbolic—here linguistic—terms.[11] This highly contextual form of communication creates a sense of community and shared experience. It is a mobilizing and forming, salient entry of the new generation into public life, which might sooner or later bring about a significant political change.[12] The new generation of voters, mothers-to-be, feminists, and activists say “get the fuck out” to a broad body of social restraints that enabled the ruling to come through and seem to hold sway over decisions of the conservative part of Polish society. For this reason, “wypierdalać” (among other profanities) has become the flagship slogan of the protests and a performative action aimed at restoring women’s right to self-determination.

[1] Aleksandra Kuźniar, “Komendant Główny Policji o protestach: zatrzymano blisko 80 osób; prowadzonych jest ponad 100 postępowań ws. dewastacji,” Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, October 29, 2020, https://www.gazetaprawna.pl/wiadomosci/artykuly/1494857,komendant-glowny-policji-o-protestach-zatrzymano-blisko-80-osob-prowadzonych-jest-ponad-100-postepowan-ws-dewastacji.html.

[2] The anonymous survey was conducted among the students of University of Warsaw.

[3] Krystyna Romanowska, “‘Chcecie zaglądać nam w majtki? Zobaczymy, kto kogo zawstydzi’. Protest kobiet to walka z pruderią,” Wysokie Obcasy, December 5, 2020, https://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/wysokie-obcasy/7,163229,26562909,mlode-kobiety-mowia-chcecie-zagladac-nam-w-majtki-to.html.

[4] Simon Worrall, “Science Says Swearing Is Good For You,” National Geographic, January 27, 2018, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/science-swearing-profanity-curse-emma-byrne.

[5] The All-Poland Women’s Strike was established in September 2016 after Polish Parliament rejected a bill “Save Women,” which constitued a response to a proposed legislation that would have introduced a total abortion ban. Protests took on various sizes and forms (for instance, women published their selfies in black clothing they wore in solidarity with the cause, as a part of Black Protests campaign). The protests were relatively successful, since they only delayed the government from passing a proposed law back in 2016. In 2020, following the Tribunal’s ruling, protests broke out again in an unprecedented form.

[6] Timothy Jay, Why We Curse. A Neuro-Psycho-Social Theory of Speech, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 2000.

[7] Agnieszka Graff, “Gdzie Się Podziały ‘Macice Wyklęte’?,” in Język Rewolucji, ed. Piotr Kosiewski (Warsaw: Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego, 2021), 23–25, http://bit.ly/Jezyk-rewolucji.

[8] On April 10, 2010 Polish aircraft crashed near the Russian city of Smoleńsk, killing all 96 people on board, including Polish president Lech Kaczyński, his wife Maria, Polish military officers, Government officials, and relatives of the victims of the Katyń massacre, the 70th anniversary of which they were supposed to commemorate. After the tragedy the political and social scene in Poland became increasingly antagonistic, also due to various conspiracy theories promoted by Law and Justice run by Jarosław Kaczyński, late president’s twin brother, who blamed the opposition, building his electorate on the tragedy’s legacy.

[9] Agnieszka Kwiatkowska, “Radykalny język protestu jako reakcja na wykluczenie i przemoc” in Język Rewolucji, ed. Piotr Kosiewski (Warsaw: Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego, 2021), 23–25, http://bit.ly/Jezyk-rewolucji.

[10] Bartek Chaciński, “Parasol dla słów” in Język Rewolucji, ed. Piotr Kosiewski (Warsaw: Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego, 2021), 37-39, http://bit.ly/Jezyk-rewolucji.

[11] Krzysztof Podemski, “Z perspektywy ‘dziadersa’” in Język Rewolucji, ed. Piotr Kosiewski (Warsaw: Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego, 2021), 31-34, http://bit.ly/Jezyk-rewolucji.

[12] According to the study published in February 2021 by the Centre for Public Opinion Research, an opinion polling institute in Poland, in 2020 the percentage of young Poles (18-24 years old) with leftist views more than doubled compared to the previous year, reaching the highest level in history (30%), and for the first time in nearly two decades, was higher than that of young Poles with right-wing views. Polish young women are primarily responsible for this record – as much as 40% identify with the left compared to 22% of men. [in:] Aleksandra Rebelińska, “CBOS: Z lewicą utożsamia się aż 40 proc. młodych Polek,” Dziennik Gazeta Prawna, March 3, 2021, https://www.gazetaprawna.pl/wiadomosci/kraj/artykuly/8111172,lewica-mlodziez-mlode-polski-cbos.html.