The future of Autonomous Factory Rog, 2021

Ljubljana

The future of Autonomous Factory Rog

On a cold wintery morning on the 19th of January, a violent eviction of the Autonomous Factory Rog (Rog for short) took place. A spacious squat in Ljubljana city center with a legacy going back almost 15-years, the Rog, nested over 20 collectives and created art studios, concert halls, a skate park and a gym, and numerous collective spaces for various activities. A former bicycle factory became a place for people looking for alternative ways of creating, organizing and being together. This essay follows the story in retrograde – departing from the destruction, leading to construction as a symbolic way of how we can see the future of alternative culture. Selected photos mark the journey of this story.

***

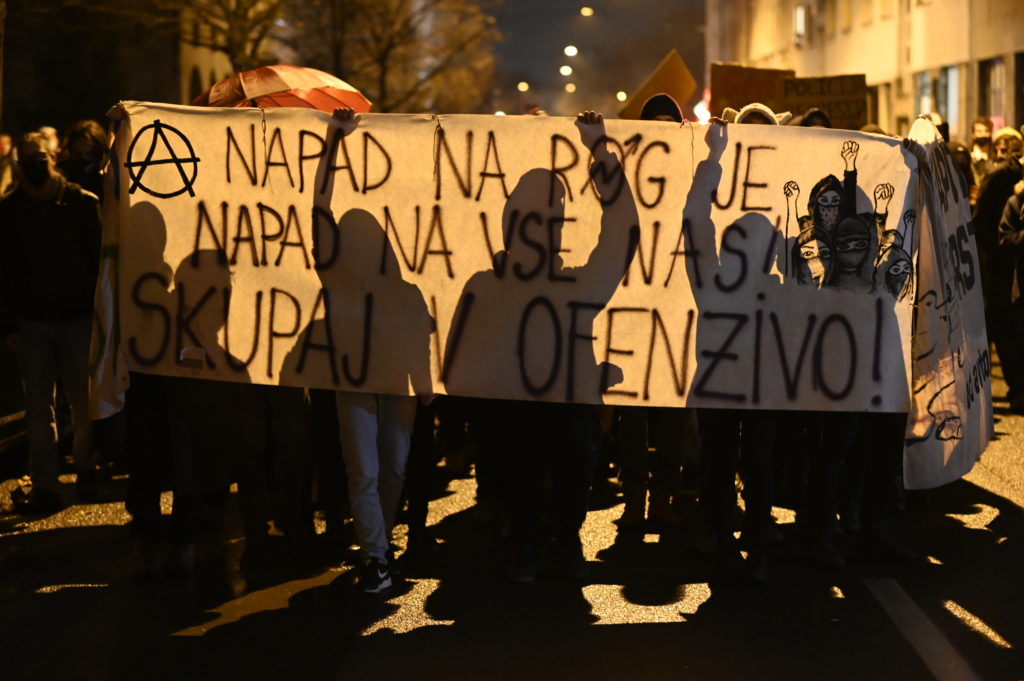

Photo of the protest from the streets of Ljubljana. The banner states: Attackon Rog is attack on all of us! Join the Offensive!

Photo: Jan Šuntajs

The starting point is the scream – an expression of outrage after the eviction. The solidarity protest that happened a few days after the eviction was widely attended, manifested that Rog had the support of the inhabitants of Ljubljana, and expressed rage against destruction of autonomous spaces. Marching people in the photo are silhouettes – physical bodies carrying a message of solidarity, putting the message in the forefront. The support was vast and visible on the streets – protests, performances and graffiti, echoed in different, traditional and social media. Scream did not come only from the people from Rog, but also from those who were shaped by activities and relations woven in one of the numerous spaces there, from those who only casually visited the night scene in Rog, as well as from artists, cultural workers and academics who valued it. The autonomous factory, Rog, was started by activists and artists who were looking to transform abandoned places into spaces of coming together in an informal and horizontal manner. Through the years, social spaces, galleries, studios, repair shops, concert halls and gyms grew from initiatives that found their home in this vast industrial complex. The main building with several floors had an open plan structure, while the smaller houses surrounding it offered spaces with more manageable sizes. In total there were around 30 spaces that were run by around 15 collectives and as many individuals, arranging their communal matters at the assembly. This main decision-making body operated on a system of direct democracy. Activities in the Rog were diverse, and this reflected in the support it received. Activists began to produce more and more Communiqués, letters of support, radio shows in a de-centralized manner trying to counter the PR machine of the municipality and mainstream discourse praising private property. It was clear that the violent takeover of Rog was a destructive act towards a marginalized community and various voices came forward to stress the importance of Rog as physical space and of Rog as an idea.

***

The eviction happened unannounced, without any warning or eviction notice. A private security company together with riot gear police dragged people from the premises and bulldozers started the demolition. Minutes after the news broke, people began to gather in front of the entrance in an attempt to prevent the eviction. They were threatened, detained, beaten, injured and pepper-sprayed. Extensive use of force was something rather new in the streets of Ljubljana. Teasers, water cannons, and pepper-sprays were rarely used against protesters in Slovenia, but several protests ended with police violence during the last year, since the right-wing government took over the political and ideological control of the country. The reason for this change on the streets does not lie in the actions of the people, but in the different ways how power manifests itself.

On the black and white photos from the eviction power can be clearly visually detected: On the one side we see a centralized hierarchical power that extends the human body with riot gear, weapons and technology, and is reinforced with machine power, whereas on the other side we see a decentralized multiplicity of bodies fueled by outrage.

Police violence against people defending Rog, solely with their bodies.

Photo: Mark Koghee

The eviction – not accidentally – happened on a wintery pandemic early morning. The social and meteorological climate was uninviting for any togetherness – the absence of a community presence created perfect conditions for the eviction. This was one of the results of months of pandemic regulations, closed cultural venues, bans on any form of public gathering and police curfew, one of the longest in Europe. In this atmosphere of almost hibernation, right-wing rhetoric was spreading from the parliament to the people, top down. The government drew international attention withits aggressive attitude towards media, culture and civil society. Their rhetoric legitimizes violent right-wing groups and enables them to operate a on the streets. By bulldozing the Rog – a place of anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-fascist and anti-capitalist politics of freedom, alternative and critical culture – the power of the government and the power of the municipality made a deal.

The “excuse” for the eviction was a total renovation – on the outside and on the inside. The central and main building with several floors was the production site of the original bicycle factory, but several smaller houses in the yard area were squatted in as well, forming a vibrant community together. The latter got demolished immediately. Their plan was to “clean” Rog of waste and dangerous chemicals (left there from the time of factory production), invest in the renovation, and then put it to use for the commercial and “creative industries” – promising studios for artists as well. By taking Rog from the squatters and claiming it, the authorities exercised their power by Foucaultian parameters of sovereignty, discipline and security. Eviction – for renovation – was in their words “for everybody’s good.”

***

While the eviction happened unexpectedly, looking from a distance, the terrain for it had been paved for a long time. The city put pressure on the Rog by pursuing legal cases against individuals, and it had even attempted the eviction five years ago. The pressure on the Rog was visually visible in the dynamic of the Ljubljana city center. In the last 15 years Ljubljana has become one of the trendiest tourist destinations; one can notice the difference by walking down the streets. Airbnbs replaced rental apartments, downtown commercial spaces became expensive tourist shops, and cafés and restaurants turned to “tourist traps.” It seems that Ljubljana’s city center is more dedicated to tourists than to its inhabitants at any time of the year. The long reach of gentrification extended towards Rog, which was indicated with last year’s renovation of Trubarjeva street – the main street connecting Rog with the main city center square. Before the actual “sterilization” of the surroundings, one could see traces of alternative culture leading towards Rog (and Metelkova Mesto[1]); graffiti and street art, posters for events and a route protestors took many times marching towards the city center.

The municipality made many earlier attempts to discipline, pressure, and evict squatters: one such incident occurred in early summer of 2016—back then, the reaction from the Rog community and its supporters was fast and powerful. Barricades and body chains stopped the bulldozers and people defended their autonomy. A bulldozer was kept hostage and became a statue, a symbol of resistance. A machine meant for demolition, for tearing down what the community built up, covered in pink color—a color associated with femininity and vulnerability—represented empowerment.

Barricades blocking uninvited demolition group.

Pink bulldozer – a symbol of resistance from the eviction attempt in 2016.

Photo: The Rog community

***

I am finishing with an image of Rog when it was autonomous – with an image of achieved possibility, concrete utopia. A possibility of a different world, different reality. The Rog was a concrete physical space and as such, it offered an opportunity for the materialization and realization of some of the most diverse initiatives. It also stood as an idea, as an ideological space, and as an invitation to open the horizon of possibilities. Can abandoned spaces in the downtown area be run by informal networks? As any other community, it had its internal challenges that were not eased by the constant pressure from the municipality. The Rog also asked: how do we come together as people? What relations do we, could we and should we create; and how can we create and shape the inseparable unity of art, politics and culture outside of capitalist relations? The Rog lent itself the opportunity to fight gentrification and turistification of Ljubljana locally, and, transnationally, today’s dominant ideologies and practices of ethno-nationalism and neoliberalism. It questioned the idea of ownership: who owns abandoned spaces and who owns the narrative on how culture in the city looks like? It questioned the city dynamic: where is the space for alternative culture in the city? Can the most vulnerable groups that were pushed to the margins of the society, such as refugees, migrants and “the Erased,”[2] find a safe space in the downtown area without becoming part of an institution? Who is welcomed in the city and on what grounds? The spirit of Rog is summed up in the graffiti painted by Italian activist and artist Blu during the rebellious summer of 2016. Skateboards, violins, books, bicycles, brains and many other tools and equipment form a gun in pink and red colors, encapsulating multiplicity of voices that found creative shelter in the Rog.

The photos presented here visually capture the narrative arch: from the nighttime photography of the scream to the dark memories of the eviction in black and white, only to be uplifted by colorful images of the resistance on barricades. The concluding panorama shot captures my framing of the eviction: to look at it from a wider perspective, placing it in the context of city politics. Today’s city plans for the Rog are part of the broader gentrification story of Ljubljana. It will lay low for a while, then re-construction will start: the space will get a new, polished look and a new identity. The discourse around the Rog will be re-constructed to mimic the biodiversity in a newly sterile environment as its harmless, attractive supplement, not a radical otherness. It would be cliché to say that the spirit of the Autonomous Factory Rog will live on, but as a matter of fact it will. People who have the physical experience of autonomy and the fight for it will in one way or another seek to continue this idea, and coming generations, encouraged by this experience, will seek it as well. Not despite gentrification but because of it—at the end a gentrified city means a future for few and a fight for the rest.

Panoramic photo of Rog after demolition on the site began.

The Rog as an autonomous and self-organized community.

Graffiti aiming critical culture at the gentrified city.

Photo: Rog community

Source: http://atrog.org/en/gallery/photo

More on Rog from Rog: http://atrog.org/en/

[1] A infamous squat of almost 30 years, located 5 minutes of walking distance from Rog.

[2] In 1991, when Slovenia gained its independence, 18.305 people were erased from the national registry of citizens – most of them from former Yugoslav republics living in Slovenia or members of Romani communities.