In the late 2000s a powerful wave of political performances came to Ukrainian art. This fascination with the language of political performance was directly connected with the aesthetics of the Orange Revolution (2004). From November 22 through December 26, 2004, Ukraine faced a large-scale wave of political protests. They were centred around Kyiv’s main square – the Maidan of Independence. One of the main problems of the era was the rapid rise of oligarchies. The country’s enormous resources fell into the hands of several warring political and economic groups. The Orange Revolution protest movement and its pre-election campaign, according to the Swedish economist and diplomat Anders Aslund, were the struggle of millionaires against billionaires.[i] But it was also the protest movement of the nascent middle class, the voice of a generation that formed after the collapse of the USSR and did not want to live in the country ruled by corrupt politicians, ultra-rich oligarchs, and gangsters.

Orange Revolution, as its name implies, had a distinct aesthetic component. Bright energetic colour became a marker of protesters and filled Ukraine’s capital and other cities. Some researchers called the events of 2004 the “Orange Visual Revolution” and interpreted them as “the destruction of the classical system of power by means of postmodern technologies.”[ii] In 2004, despite the unprecedented concentration of people in the centre of Kyiv and their rebellious? moods, the situation was non-violent. The main tool of political resistance was artistic expression: folk performances, costume marches with their specific humour, slogans, and songs.

The whole revolution was in fact one big street performance. It was a political protest with folk carnivalesque ritual elements which overturns the official hierarchy and restores the mythical golden age of universal equality. Mikhail Bakhtin’s conceptualization of carnivalesque as a temporary reversal of power relations (which in the end reinforces social order) might be helpful for understanding the situation in Ukraine in 2004.[iii] It was in this atmosphere that a new generation of artists entered the scene.

In 2009, a new self-organized art space appeared in Kyiv that would prove very important for the generation of the Ukrainian artists of the late 2000s. It was created by Artur Belozerov, a member of both an influential young art activist collective “REP” and the local party scene. He worked in collaboration with another former member of REP, Borys Kashapov, who was also known under the pseudonym Andrusha Kremov. Their punk gallery LabGarage was situated in a garage cooperative on Velyka Zhytomyrska Street, near Peizazhna Alley, a promenade beloved by Kyivans. It was not a serious or rigorous institution, rather a space of freedom and buffoonery, characterized by spontaneity and a resistance to structure. Despite this, the LabGarage contrived to put on entirely classical chamber exhibitions, concerts, lecture courses, and film viewings. The most striking exhibitions created by LabGarage included the art project Society’s Member by Andriusha Kremov, Masha Pavlenko’s show V kontakte (In contact), as well as Artur Belozerov’s installation Bourgeoisie, Bourgeois Some More (2009).

The flamboyant artist Belozerov also redefined a typical feature of the urban landscape: the dumpster. The banal dumpster became a metaphor for consumerist society, which both the artist himself and the “antiglamor-anticrisis” LabGarage were opposed to. The dumpster was transformed by Belozerov into a luxury Jacuzzi bath, priced at 15,000 euros. The artist was poking fun at the sky-high prices in contemporary art in post-crisis Ukraine. The art group TOPORKESTRA, another memorable art phenomenon from this period, performed at the opening of the project. In the 1980s and 1990s, exhibition openings in Kyiv rarely took place without the appearance of an iconic artist, performer and city personality Fedir Tetianych. In the same way, it was rare for TOPORKESTRA to not appear at an art event in the city in the late 2000s and 2010s; they were an elemental and daring collective of musicians, whose leader, visual artist by education Serhii Topor had at some point also trained as a performance artist. The calling card of that decade’s most spontaneous, non-mainstream, and artistic musical collective was loud music, unbridled fun, and, of course, the neighbors calling the police.

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBJ030rrmbQ )

The second half of the 2000s saw the emergence of art projects that combined music and contemporary performance. This included the legendary group Penoplast (Styrofoam), whose provocative performances in the second half of the 2000s involved many members of that period’s art scene. Active members of Penoplast included Anatolii Belov and Zhanna Kadyrova. Artur Belozerov was one of the leaders of the group, and the creator of the “trash hit,” Rinat, Give Me a Billion, which was dedicated to a certain odious Ukrainian oligarch. The group’s most memorable member, the “face” of Penoplast, was Don Pedros (Serhii Demchuk). An idiosyncratic outsider-figure, who was old enough to be the father of the rest of the group and had worked previously as a journalist, he made his living selling plastic bags on trains and he was practically never sober when in public.

Within the context of the late 2000s, it is important to include the kings of Ukrainian camp, the provocative performance group Khammerman Znyshchuie Virusy (Hammerman Destroys Viruses). This collective was founded in 1996 in Sumakh. By 2004, when Hammerman’s first relatively successful music album Pop Star was released, the group was made up of the duo of Volodymyr Pakholiuk and Albert Tsukrenko. The group’s critical and provocative texts were dedicated to the acute social problems facing post-Soviet society, namely low-paid office work, alcoholism, corrupt politicians, the growing role of the church, and the double standards of its followers.

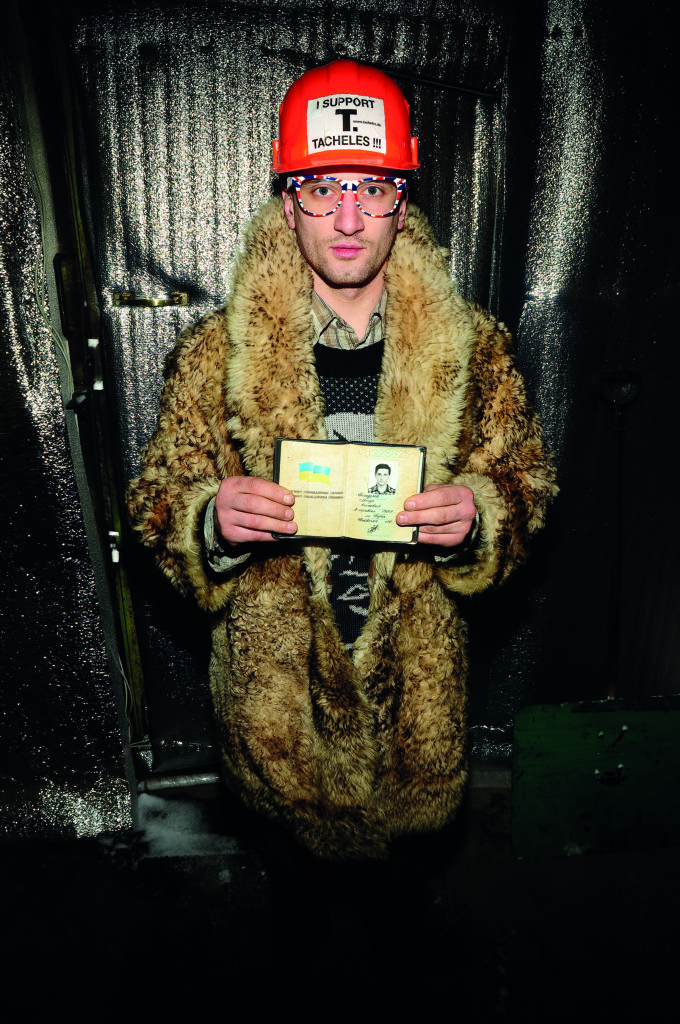

The lyrical hero of most of Hammerman’s compositions was an imagined member of Ukraine’s creative class, which harbored its own creative ambitions, while also slaving away at a “normal” job. Of course, this was entirely autobiographical; the group’s members earned their living as journalists. Pakholiuk and Tsukrenko included Surzhyk,[iv] the living, breathing voice of the people, in their compositions. They were also not afraid of producing work of a low musical quality. Every performance by the group turned into a show with its own pre-prepared theme and range of costumes worn by the artists. The costumes stood out for their trashiness, irony, and also for the particular artistry that was unique to the group. The performers’ otherworldly aesthetic and sense of mockery, borrowed from queer culture, sat alongside their cis-gender identity and their reverence for family values, upon which they placed particular emphasis. For a long time, Hammerman existed in parallel to contemporary artistic society, and it was only by the mid-2010s that the gap began to narrow. Some of the group’s most famous shows from the end of the 2000s included performing in funeral wreaths with nothing on underneath, and also while wearing Orthodox icons.

The protest performance was another art phenomenon from the second half of the 2000s. The experience of the color revolutions demonstrated the effectiveness of the artistic act and its viral nature in the media. The expansion of the internet saw the growth in popularity of striking, calculated artistic statements that were geared towards an online audience. In neighboring Russia, the group Voina (War) came to be known for their art actions which criticized those in power. Attempts to use the language of contemporary performance as a way to engage with both political and social problems also began to appear in Ukraine.

One of the most popular protest statements organized by members of the country’s art scene was Lie and Wait. The action was carried out by Mykola Ridnyi, a participant of the SOSka group with the help of Ivonna Holybievska. For a Ukrainian citizen applying for the European and especially German visa was a challenging and rather humiliating process at this time. It was especially difficult for young artists. In 2006, after the artist had been refused a European visa several times in a row, Ridnyi laid on the sidewalk in front of the German embassy in protest, after which he was detained by diplomatic security. The project was inspired by the artist’s real experience of being unable to obtain a visa despite having an invitation to his own exhibition in Europe. The humiliating process of drawing up the correct documents to visit Europe, a place traversed by almost every traveler, sat in sharp contrast to politicians’ rhetoric about European integration and demonstrated the true attitude of the European Union towards Ukraine and its citizens.

At the beginning of 2008, the exhibition Common Space was opened in a freight container at the Arsenalna metro station in Kyiv. Its participants included REP and the Russian art group Voina. Video footage of FEAST (PIR), an art action by Voina, was shown at the exhibition alongside other art pieces. FEAST was originally organized in 2007 in memory of the artist and writer Dmitrii Aleksandrovich Prigov. Voina invaded the public sphere and set up a sumptuous commemoration for the leader of Russian unofficial art directly in a carriage of the Moscow metro. The Kyiv authorities destroyed the Common Space exhibition, just two days after it opened, and dismantled the freight container in which it had been held. In a show of protest, the exhibition’s organizers decided to carry out their own FEAST art action on the three lines of the Kyiv metro. This analogous “invasion” took place on February 10, 2008. Members of REP, along with the Kyiv counterculture writer Adolfych, took part alongside the Voina group.

The Femen group was a controversial art phenomenon from the end of the 2000s. Their work combined elements of contemporary art, media spectacle, and political provocation. Despite the warm reception the group received in Europe, France in particular, the group was never accepted within the contemporary art scene in Ukraine. In fact, the sole stunt connected to figurative art that the group performed just demonstrated the hostility of Femen’s members towards contemporary artistic practice. Femen was initially launched as a media provocation project solely created to breathe some life into the endless stream of Ukrainian political TV shows. On February 2, 2010, Femen activists started a protest in the PinchukArtCentre wearing nothing but their underwear. They were protesting Serhii Bratkov’s ambiguous artwork Khortytsia, which depicted a girl in national Ukrainian costume with exposed genitals. The naked protestors, wearing Ukrainian national garlands on their heads, held up placards with the words “Ukraine is not a Vagina!” and “VaginArt!”, which, in the context of Femen’s strategy of provocatively utilizing their naked bodies, only served to highlight the absurdity of what was happening. This conservative outcry did not aim to dig deep into the ideas behind the artwork – it was a simple, visually catchy and effective media provocation and one of the few incidents where Femen, who mainly targeted politicians, actually interacted with Ukrainian artistic community.

Oleksandr Volodarsky’s (also known as Shiitman) art action in front of the Verkhovna Rada, the Ukrainian Parliament also ended in scandal. Oleksandr, an artist and blogger from Luhansk, together with a member of a radical art group he created, imitated a sex act next to the building.

This was in protest against the actions of the National Expert Commission on the Protection of Public Morality – a highly controversial newly created official institution aimed to promote ultra-conservative agenda in culture and arts. Criminal charges were consequently brought against the artist for disorderly conduct, and as a result he spent five months in a prison colony. On 29 September 2010, spurred on by his experience with criminal investigators, Volodarsky organized the art action You’re Not in Europe Any More. The phrase was then tattooed onto the artist’s back without any ink, and was, in his opinion, the perfect image to encapsulate the working principles of the Ukrainian law enforcement agencies.

In the 2000s, artists weren’t only interested in performance as a form of protest. Artists such as Myroslav Vaida appeared on the scene, and from 2008 the annual Performance. Days of Art was held in Lviv, headed by Vlodko Kaufman. The independent research collective TanzLaboratorium was an important group at this time, balancing on the border between performance and contemporary dance. Larysa Venediktova, Olha Komisar (Savchenko), and Oleksandr Lebedev were at the core of this group. TanzLaboratorium formally existed from the early 2000s,though the peak of the group’s activity within the contemporary art scene occurred at the beginning of the 2010s. The collective’s central themes were the body and its imagination, time, and also dance as a form of thought.

Alevtina Kakhidze was an artist whose art projects often included a performative element. Her performance I Am Late for a Plane for Which It Is Impossible to Be Late took place in 2010. As part of a newly founded grant program from a foundation set up by the oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, she gained permission to take a flight in a chartered plane owned by an unnamed individual. This project marked the continuation of her 2008 exhibition, in which Kakhidze wrote letters directly to several oligarchs that contained the following words: “I am an artist. When I am asked if I can paint someone’s portrait, a still life, or the sea, I always reply that I can draw anything. Rather, that is what I used to say. Now I don’t say that. The issue is that I discovered there is one thing I cannot draw. I cannot draw the earth, as if drawn while looking out the window of my own private plane.” After completing the flight, the artist held a press conference and told everyone who gathered all the details of how the project came about. No drawing was made as a result of sitting on board the airplane. This succeeded in destroying the stereotype of the artist and their social role and prompted a negative reaction from the public. The artist’s flight in a private plane, paid for by a businessman with a questionable reputation, and her refusal to create a “work of art” in the traditional sense of the word, was an excellent illustration of the contradictions inherent in the young Ukrainian art scene at the end of the 2000s and beginning of the 2010s when artists both embraced the activist agenda and were collaborating with institutions created for the oligarchic money (such as Pinchuk Art centre, Ukraine’s main private art institution, created for the money of one of Ukraine’s richest people, Viktor Pinchuk or the grant program offered by an ultra rich and highly ambiguous businessman Rinat Akhmetov.

[i] Aslund, Anders. Ukraine Whole and Free: What I saw at the orange revolution. The Weekly Standard. 27.12.2004

[ii] Родькин Павел. Оранжевая визуальная революция. Фирменные стили. против символических систем. Эскалация дизайна и эскалация. власти. Москва, 2005.

[iii] Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and his world. Indiana University Press, 1984

[iv] A term that refers to a sociolect that mixes Ukrainian and Russian.