E. Susanna Weygandt

Documentary dramas, or docudramas, are plays that are based on reported speech from interviews with people of marginalized social groups. In Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Deleuze and Guarttari write, “reality is what actually happens in a factory, in a school, in barracks, in a prison, in a police station” (1977, 212). Marginalized social groups represented in New Drama plays include those whose voices are from the factory, school, barracks, prison, or police station (often for unjust charges). They are the voices that are silenced in the news and in political debate. New Drama’s hero belongs to the subaltern and through the subaltern the audience or reader receives insight about this reality of the post-Soviet setting. With the help of digital technology, Russian docudramas convey real speech in a play without re-motivating it by the stylization of the author’s hand. Docudrama manifestos state that this form of performance emerged specifically for the purpose of voicing “direct utterance” (priamoe vyskazyvanie) about societal problems. When reported recorded speech hits the stage, it doesn’t flatten into reportage, rather, it equates to “enunciation” that, as Henri LeFebvre describes “situates the act of everyday practice and use of language in relation to its circumstances.” It is the type of “enunciation” that “establishes a present through the act of the ‘I’ who speaks, and conjointly, since the present is properly the source of time, it is also the organization of a temporality (the present creates a before and an after) and the existence of a ‘now’ which is the presence of the world” (The Production of Space, 33). The language of recorded interviews with people of contemporary subcultures has become one of the preferred forms of expression for its ability to not only reflect the post-Soviet condition but also to reproduce the condition of the contemporary environment through recorded, reported speech.

The playwright, who is also the actor in the docudrama play, takes the digital voice recorder out to the dwelling place of a marginalized social group and asks questions. Docudrama, as a dramatic style, originated in the United Kingdom in the work of Alecky Blythe and is associated widely with Eve Endler’s Vagina Monologues (US). British docudrama was developed outside of London mainstream theatres in the atmosphere of a growing interest in collectivism and community. Docudrama spread to Russian theatre after playwrights and directors from the Royal Court Theatre in London in 1999 went to Moscow to teach the method. The playwrights Mikhail Durnenkov, Ivan Vyrypaev, Elena Gremina and Mikhail Ugarov attended the first seminars. By now documentary drama is a transnational movement used notably in Belarus, at Belarus Free Theatre, where Russian is the most commonly used language, and in Ukraine, at Theatre of Displaced People, where the use of Russian was relatively unproblematic until the occupation of Crimea and the civil discord within Ukraine rendered it a contentious issue. While the first seminars by the Royal Court in 1999 were recorded and the lessons were quickly shared, the documentary drama method connects to earlier forms in the Russian canon. Since 2002, docudramatists in Russia, and particularly at Teatr.doc, a theatre considered the flagship of Russian docudrama, has defied legislation banning the use of obscenity on stage; it examines social issues such as homosexuality; it transgresses socially conservative boundaries relating to religion and blasphemy; it explores crime, youth disaffection and violence in post-Soviet societies; it has explored taboo scandals of political corruption and police brutality; and it has resisted attempts to impose monologic narratives about socio-historical issues.

Indeed it is logical to presume that when social critique is fostered in the theatre, the theatre can be a gateway for larger activist movement on the street. Actors, playwrights, and audience members might not run straight to a volunteer organization after each show, but regularly several do take part in subbotniki (Saturdays-ings), community and volunteer work that takes place on Saturdays, a tradition practiced in Soviet Russia, now rekindled by Teatr.doc. Teatr.doc has had a significant impact on the young generation, which, between 2010 and Putin’s reelection in 2012, began Russia’s most serious protest movement in the past three decades (Crowd sizes grew as much as 100,000 or more, until the great crackdown that took place on May 6, 2012, the day before the inauguration of Putin to a third term). Docudramatists collaborate with one another and also with other social activist artists, including Pavel Pavlensky, his partner Olga Shalygina, and with Pussy Riot, and so docudrama’s aesthetics of the stage can be placed in the broader context of popular contemporary culture. Exercises of social critique and dissent against Putin were practiced at Teatr.doc in, most ostensibly, Bolotnoe Delo (2015), about those imprisoned after protesting Putin’s unconstitutional third term as President, and BerlusPutin (2012)about a ruling creature who is half Silvio Berlusconi, Italian media tycoon and politician, and half Vladimir Putin. These performances and others have also led to this theatre experiencing many threats from Moscow police and even enforced closures.

Both British and Russian verbatim theaters share an interest in using their theater to bring attention to social struggles. There are, however, some differences between British and Russian verbatim docudrama, but the main one is that in Russia there are repercussions of touching the real that do not occur in the UK or Western countries. In 2014 new laws were passed in Russia censoring profanitiesand public dissent against Putin, as a result of the cultural conservatism of Putin’s current administration. Without notice, police raided Teatr.doc’s basement studio on Trukhprudnyi street (a twenty-minute walk from Red Square) in February 2015 and confiscated material – scripts and the laptop of a director who works at Teatr.doc. In March 2015 Teatr.doc relocated to a theatre outside of Moscow’s center – to Razguliae Square. Over the next few months Teatr.doc members with help of volunteers converted a dilapidated basement into a theatre studio with their own hands. Once it was finished, in May of 2015, they were evicted from that space too, but have since secured a new theatre in Moscow’s center. Then, once again, Teatr.doc was forced to move premises, and it is now established in two separate locations, one on Sadovnicheskaia Embankment (named ‘Doc on the Island’) and the other in a newer space just behind the Gogol’ Center on Malyi Kazennyi Alley. This is also where Moscow’s Liubimovka Festival took place in early September 2019. In the dream of an intimate setting of a new basement, Teatr.doc wants to bring people together again to stage, analyze, reflect on, and discuss social problems in everyday life.

The former police raids have only widened docudrama’s popularity and power. As Teatr.doc has been leading the verbatim movement since its inception in Russia and since many docudrama manifestos originated there, I will focus on this theater. Here I will mention the composition of two plays, September.doc (2004), written by the late Elena Gremina and Mikhail Ugarov, and the sequel to September.doc that is titled, Novaia Antigona (2016), an adaptation of Sophocles’s tragedy found by docudramatists to be an appropriate sequel of September.doc. Both plays were also staged at Teatr.doc. When the document hits the stage, the effect does not flatten into reportage, nor does it create an overt political message. Instead, the document is presented within the arrangement of original artistic strategies, and these artistic strategies to create a participatory art with heightened audience engagement.

September.Doc was written in response to the 2004 Beslan tragedy when school children and teachers in North Ossetia were killed by Chechen and Ingush terrorists and subsequent Russian counter-terrorist intervention. The playwrights collected seventy-seven text fragments of Chechen and Russian open-editorials and purported eye-witness accounts posted on Internet blogs after the tragedy and then compiled them into a montage. The Russians’ and the Chechens’ direct quotes in September.doc are charged with loss of innocence and racial prejudice. Even the unauthored texts found around the area of Northern Ossetia after the tragedy and which were then inserted in the play – “Wanted” ads for the prized capture of Russian army generals, lists of dead soldiers, and even an unauthored poem entitled, “You’re Alive but I’m Dead” – add to emotional build-up. Even though the text on the Blogs cannot be officially traced to real people, the issues of Russian-Chechen conflict and racism that stand behind this text are real. Through artistic devices such as montaging texts according to emotions, she and other docudramatists attempt to order reality into a conception that will make an impact on the audience.

In 2016 the mothers who had lost their children took to the streets in Beslan to demonstrate and make public the lack of justice that the court provided after the terrorist attack. The mothers demanded punishment for those who organized the terrorist attack. The women were arrested. According to police, they no longer have the right to grieve or blame. Given the sensitive nature of this event, Elena Gremina had to think carefully about how to approach it, in the end choosing to reach back myth, and she named the new play Novaia Antigona. The play combines recorded accounts and testimonies of the mothers and also includes sections of text from Sophocles’s Antigone. 2500 years ago Sophocles wrote the tragedy Antigone about a young woman who stood up to the ruling power in order to follow her conscious and honor her family. The Greek tragedy explores themes such as state control versus natural law. For the protagonist of Antigone the honor to her family outweighs her duties to the state.

Antigone’s defiance of the laws of Creon and the state come alive in Teatr.doc’s Novaia Antigona. Teatr.doc’s play also shows us that documentation is not at all opposed to myth-making, both ideological and individual. Although synthesizing myth and the documentary in a docudrama performance such as Novaia Antigona seems contradictory, since one is almost entirely fictive and the other is based on real-life, myth is not wholly contrived or “false.” There are many literary theories about myth. One definition pertinent to this study is Claude Levi-Strauss’s “The Structure and Form of Myth” (1955). In his essay, Levi-Strauss explains that 1) Myths can organize a society into a structure that exposes contradictions in it. 2) Myths that can resolve the conflicts might not be straightforwardly representative of one specific historical era only because they relate to both the context from which they derive and can relate to the future. “Mythical time,” according to Levi-Strauss,[1] is a double structure – it can be used among other cultures. Russian docudrama uses Antigone’s natural law to make sense of real life by apply a moral code to it. In this same way, Russian docudrama has the potential to be an enduring literature, too.

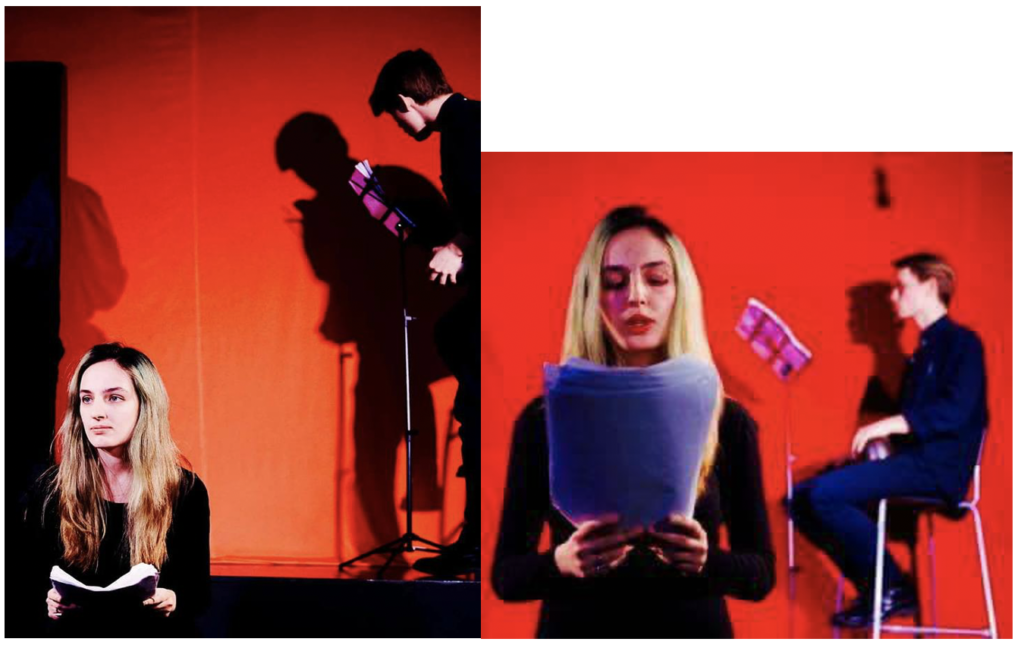

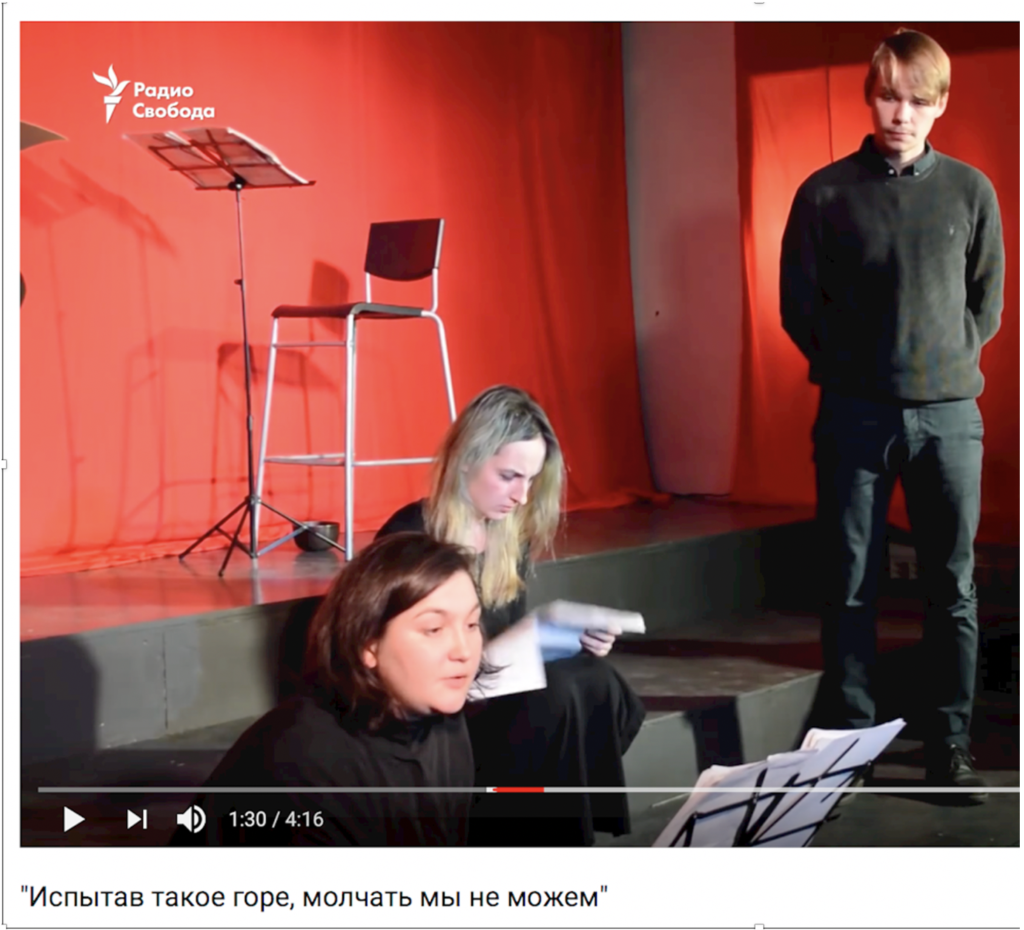

Scene one of Novaia Antigona directed by Elena Gremina

1. Судья. Так, хорошо. Давайте исследуем материалы дела, те же рапорта. Рапорт Князьева, который вы изучали, рапорт Клиева, из которого усматриваем, что граждане Тагаева, Цирихова, в майках «Путин – палач» выкрикивали в толпу лозунги «Вы убийцы наших детей». Для пресечения противоправных действий был вызван наряд, при проведении к машине оказали сопротивление. Письма новой администрации Правобережного района о том, что не поступали к ним заявки на проведение публичных мероприятий, и точно также от главы местного самоуправления Бесланского городского поселения. Это таблица, в которой усматривается, что… где вы здесь в таблице?

Эмма. Я не знаю.

Судья. Подойдите, посмотрите на фотографии.

Paraphrased in English:

Above is the text reported verbatim by the journalist Elena Kostiuchenko. A judge reports about how Ms. Tagaeva and Ms. Tsirikova demonstrated in t-shirts with the slogans “Putin is the Executioner of Beslan.” The judge points out that the women didn’t file for permission to hold a protest.

Scene two of Novaia Antigona directed by Elena Gremina

2. Эмма Тагаева. Ее мужа Руслана расстреляли в первый день

– вместе с остальными мужчинами.

Ее сыновья – 16 летний Алан и 13-летний Аслан

видели убийство отца.

Они смогли проползти в соседнюю комнату, где лежали тела,

и сутки сиделvи над трупом отца. Они прожили еще два дня.

Аслан сгорел в школе.

Алан выбежал, добежал до гаражей, там присел и сполз.

Через него перепрыгивали убегающие дети.

Они встречались взглядами, и поэтому они запомнили Алана.

Его убили во время штурма встречными выстрелами.

Эмма сама обследовала тело сына.

Говорит, тело было чистым –

только две маленькие ранки – в коленке и в животе.

В справке о смерти десятиклассника Алана, умершего в проходе между гаражами, указано, что 60% тела обожжено, а смерть наступила в результате взрыва. […]

The above paraphrased in English:

A chorus sings a requiem-like composition about the shooting of one woman’s husband as witnessed by her sons, before the sons themselves were killed.

Post-show Q & A with audience, a part of every premiere of a docudrama play at Teatr.doc:

Андрей Демидов: Акция с футболками была отчаянным жестом этого меньшинства (the group of women). Государство отреагировало как обычно, но необычным был контекст. Осуждены матери, потерявшие своих детей при самых страшных, какие только можно представить, обстоятельствах. Осуждены за явно ненасильственные, не имеющие малейшей общественной угрозы действия. За то, что на месте гибели своих детей позволили себе обвинить в гибели детей президента. И здесь первая параллель с сюжетом Антигоны. Бесчеловечный формальный закон входит в противоречие с живым человеческим законом — законом сострадания.

The above paraphrased in English:

The audience member, Andrei Demidov, points out the parallel between Sophicles’s Antigone and Teatr.doc’s Novaya Antigona: “An unhuman law contradicts a live human law, the law of mercy and compassion.”

.

Teatr.doc, in Moscow, is a hub of political art-making. On March 8, 2016 Teatr.doc hosted a Question-&-Answer session with Olga Shalygina, who is the wife of protest-artist Pavel Pavlensky. He was also interviewed at Teatr.doc by the late Mikhail Ugarov, Teatr.doc co-founder.